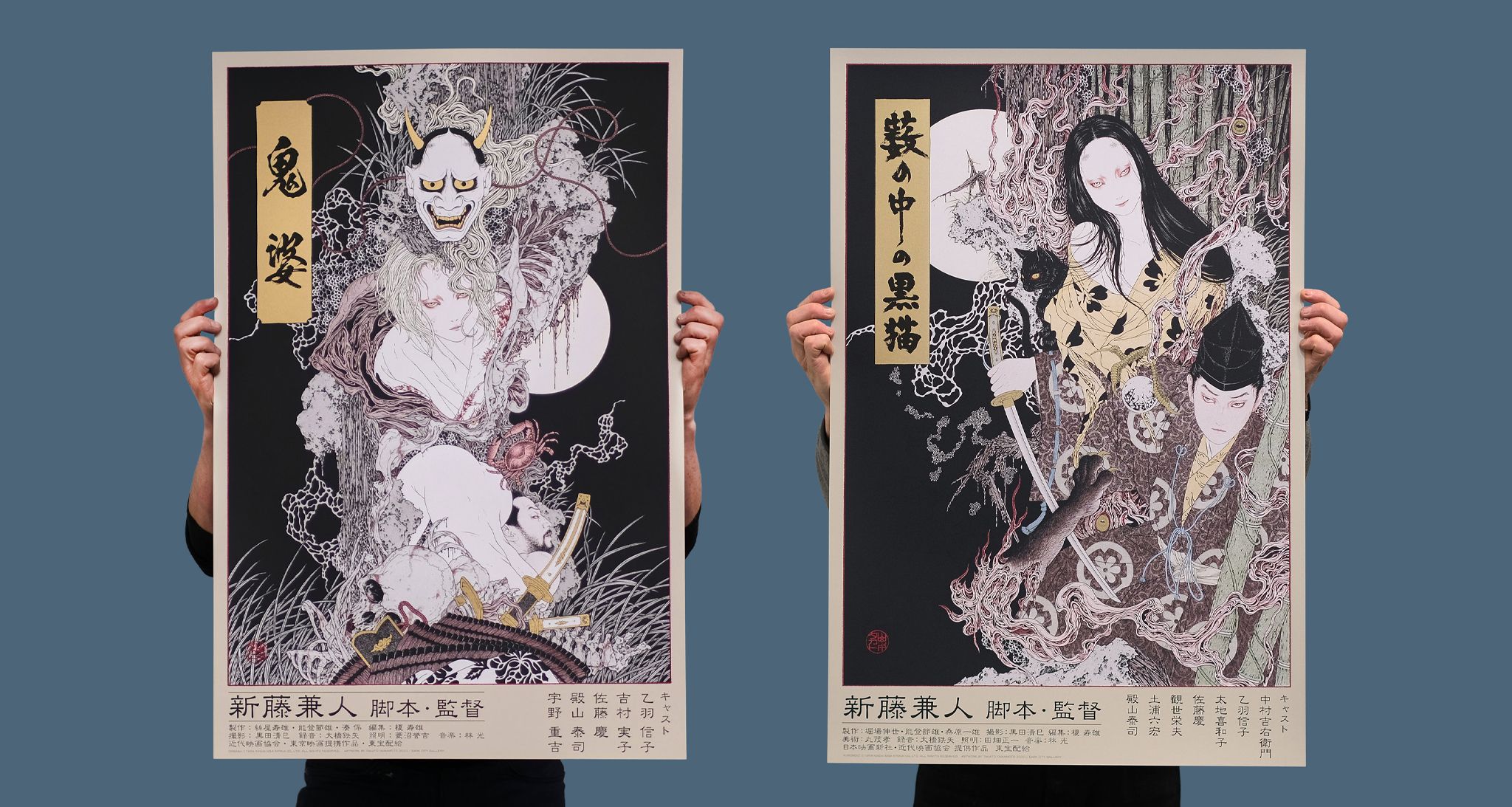

Onibaba and Kuroneko, screenprinted alt. movie posters by Takato Yamamoto

Dark City Gallery go to the source, employing a revered Japanese artist whose roots lie in the ukiyo-e tradition to create posters for Kaneto Shindô's iconic horror films

Onibaba and Kuroneko are a double pair of posters by Japanese artist Takato Yamamoto, commissioned and released by Dark City Gallery in the UK to kick off what will be an ongoing series of Japanese film posters.

It was something of a coup for Dark City Gallery to enlist the considerable talent of Takato Yamamoto, revered as he is in his home country of Japan for an art style that began in the ukiyo-e tradition and soon evolved into an instantly recognisable aesthetic all his own. The tenacious move on the gallery’s part was in pairing Onibaba and Kuroneko—the intrinsically linked horror films by celebrated director Kaneto Shindô—with a reputable Japanese artist who had previously never worked on an alt. movie poster.

From afar, it could be read as a risky move. Either that or a crystalline masterstroke.

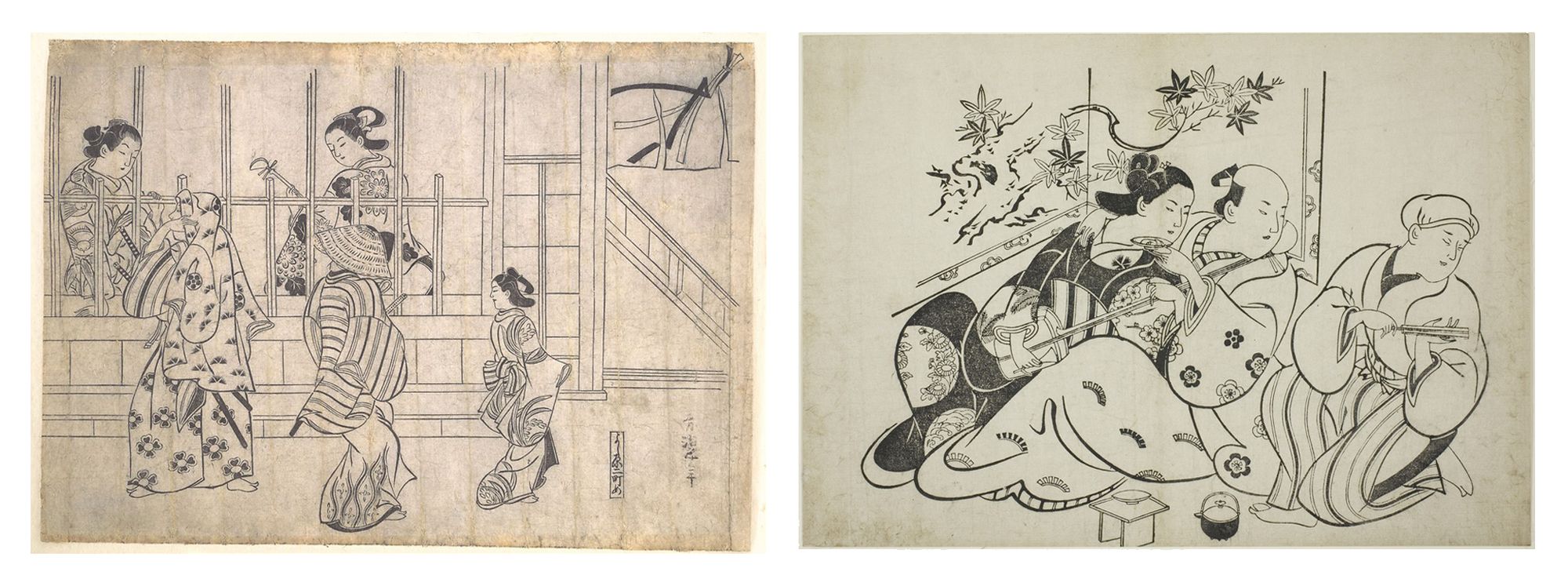

Takato Yamamoto spent the early part of his career honing his skills in the ukiyo-e style, a celebrated art tradition that established itself in Japan during the Edo period. This period is recognised as a prosperous time that ran for some 260 years from around 1600.

The newly born culture of the Edo period had the Japanese name ukiyo, the early meaning of which represented the struggle on earth when compared with conditions in heaven. Over time the meaning of ukiyo transmuted to floating world, a phrase birthed in the red-light district of Yoshiwara and imbued with the hedonism of the era.

“Employing an artist who heralds from the ukiyo-e tradition to create a modern-day movie poster is not such a great leap from the original intent of their artistry.”

Floating world suggested at literal heaven on earth brought about by prosperity, but as appreciation for society blossomed—a beautiful new state of social life emerging like the slowly opening petals of a rarified orchid—the word ukiyo further evolved to mean current modern style, a prevailing way of thinking in a positive manner.

As a means of expressing this mood, the ukiyo-e art style and its associated prints came into being—ukiyo-e meaning pictures of the floating world. Alongside depictions of myth and folklore and acts of great heroism, ukiyo-e prints would draw on subjects and topics from the forefront of society, focusing the halcyon days of the present and literally showing the common people of the Edo era what their social life was like.

Within this mode, bijan-ga were prints of beautiful women and yakusha-e were prints of kabuki actors, but fundamentally, ukiyo-e conveyed the era’s way of life, upholding its beauty and simultaneously selling its irresistible allure.

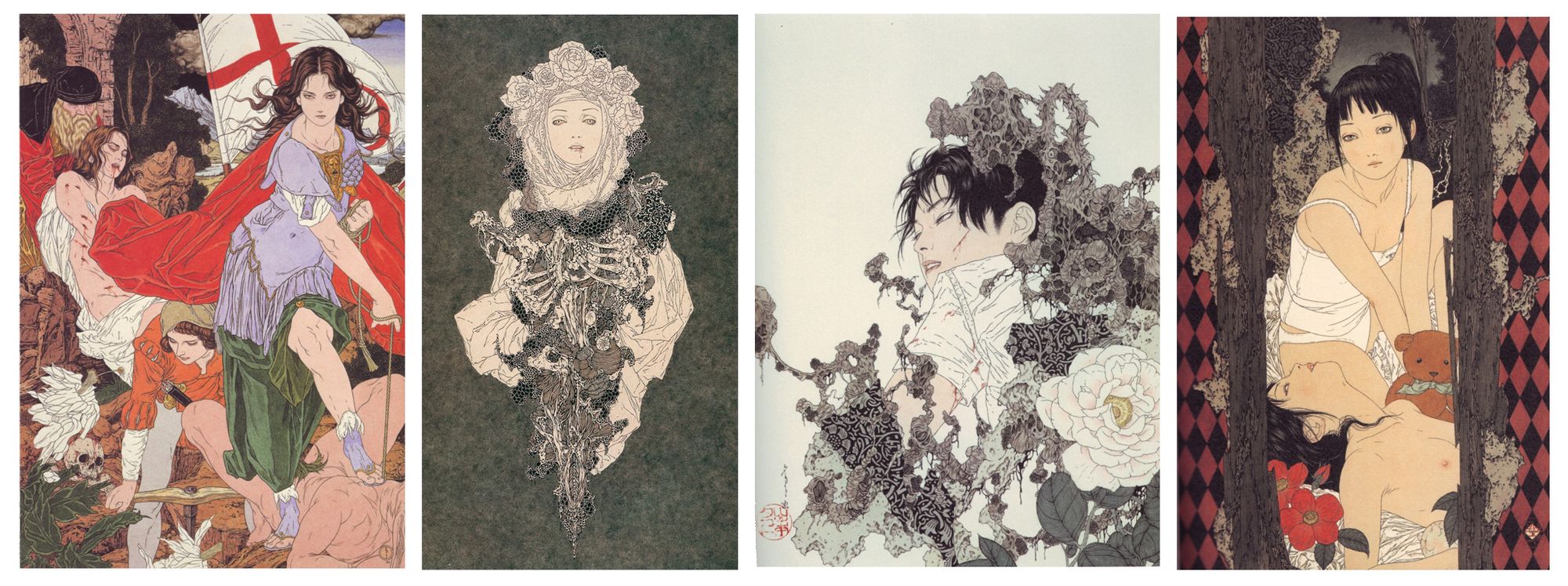

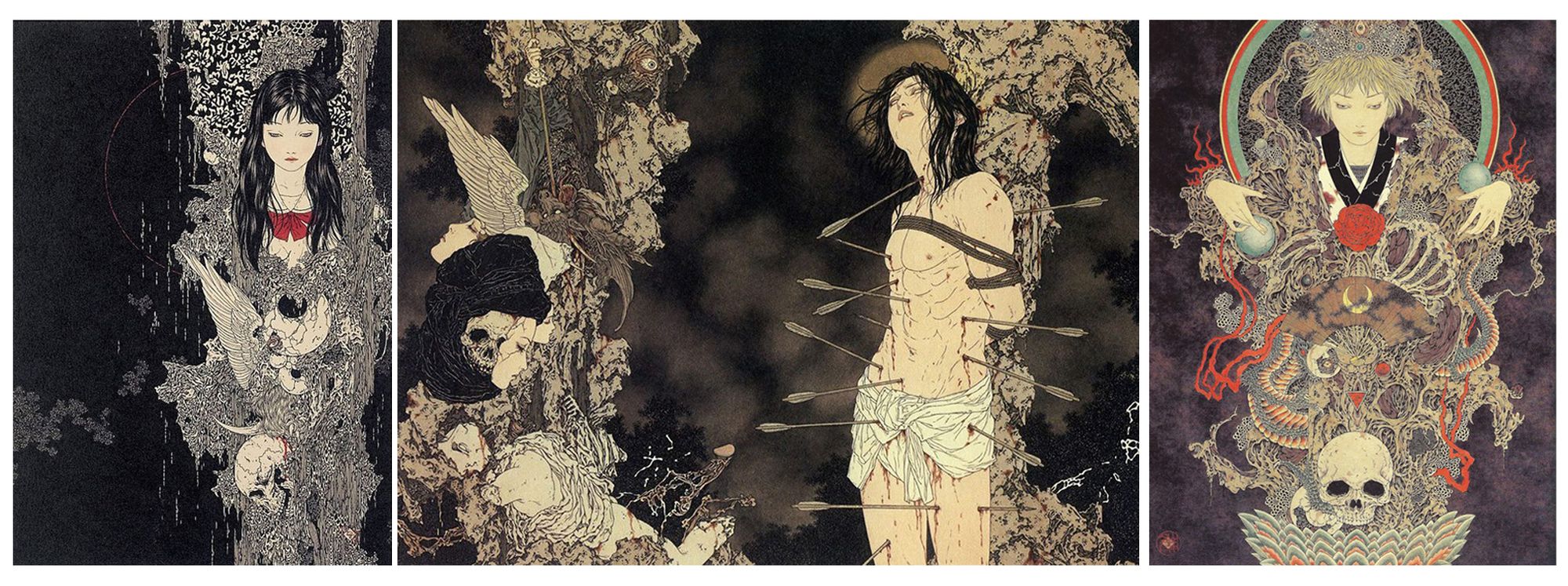

While Takato Yamamoto may have honed his craft in the tradition of the ukiyo-e artists who came before him, he found his voice when moving beyond the medium and establishing his own style. This he dubbed Heisei Estheticism—a mixture of “ukiyo-e, manga, and contemporary gothic horror.”

As well as sheer technical prowess, the artist’s stylistic voice became known for its darker and more subversive themes, as well as its “sensual portrayal of women” and the repeat exploration of “vampiric” and “Lolita-esque” figures.

With an audience rapidly gathering, Yamamoto staged his debut solo show in 1998, at Creation Gallery G8 in the Ginza district of Toyko.

It is perhaps Yamamoto’s Heisei Estheticism that makes him such a cohesive pairing with Kaneto Shindô’s iconic films.

Released in 1964 and 1968 respectively, and both starring the filmmaker’s longtime muse, Nobuko Otowa, Onibaba and Kuroneko are singular works, renowned for good reason. Award-winning in both acting and cinematography categories (Shindô enjoyed a long-running partnership with renowned cinematographer Kiyomi Kuroda), the films are visually stunning and have an arresting poeticism to their tone and pace.

“If one looks back at Yamamoto’s earlier work, it is clear that many of his identifiers are to be found in these new artworks, perfectly interwoven with the narratives and characters made recognisable by the films.”

Though dealing in themes of class struggle, revenge and recompense, and the transmutation of one’s humanity during times of great duress, overwhelmingly there are energetic forces at work in Shindô’s films. Deep, brooding, carnal forces. In the director’s own assessment, a “sexual energy” exists, necessary to the sustaining of one’s survival.

This energy within the films, with its underlying eroticism set against bare-bones survival, is to what Yamamoto’s aesthetic speaks so keenly.

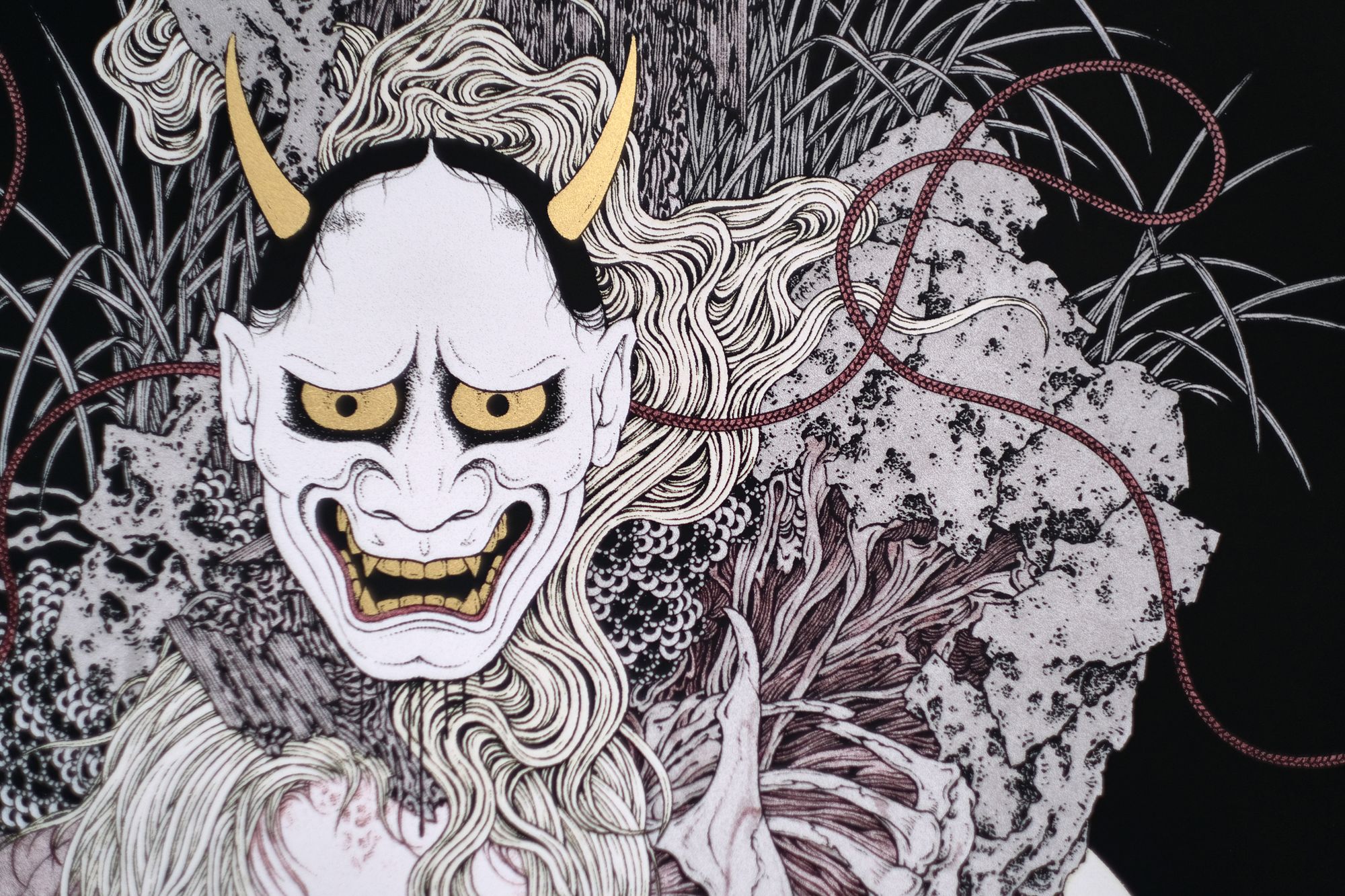

In the poster for Onibaba, Yamamoto condenses the necessity for sexual encounter and macabre reality of the film, stacking the characters in an almost morbid purgatorial totem, with bones and skulls at its base, hinting at the unseen fathom of the hole, and at its crown the hannya mask, demonic yet sorrowful, clouding the humanity of any woman or man who wears it. Wrought throughout are the reeds, the artist’s signature formations of stone and sinewy entrails, various armatures, and the enveloping pitch blackness of a nowhere place, the events therein playing out while time appears to stand still.

The posters, like the films, have a great deal in common, sharing composition and framing, likenesses and attitudes, and the same piercing outward-looking engagement of their indelible characterisations. If one looks back at Yamamoto’s earlier work, it is clear that many of his identifiers are to be found in these new artworks, perfectly interwoven with the narratives and characters made recognisable by the films.

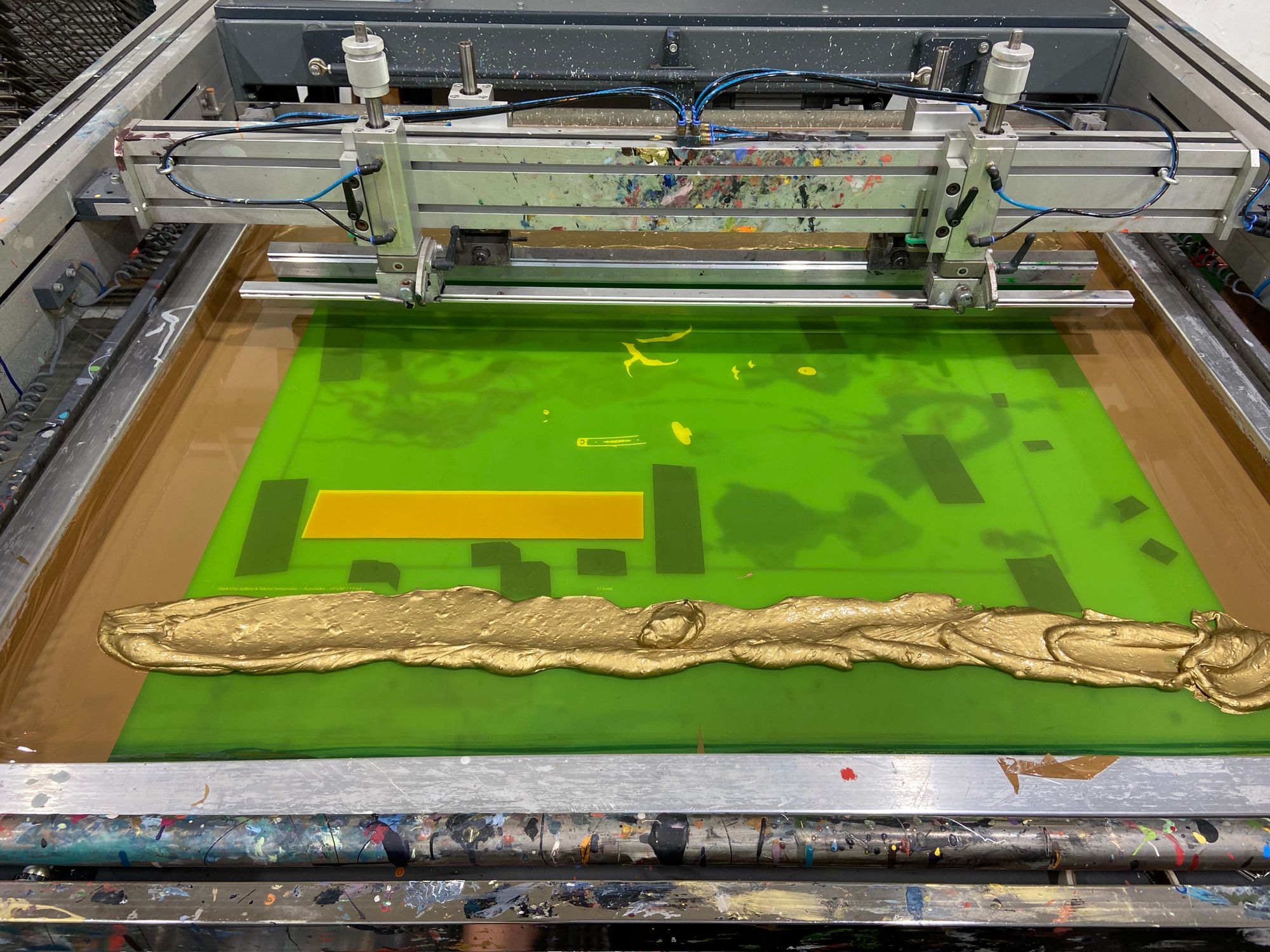

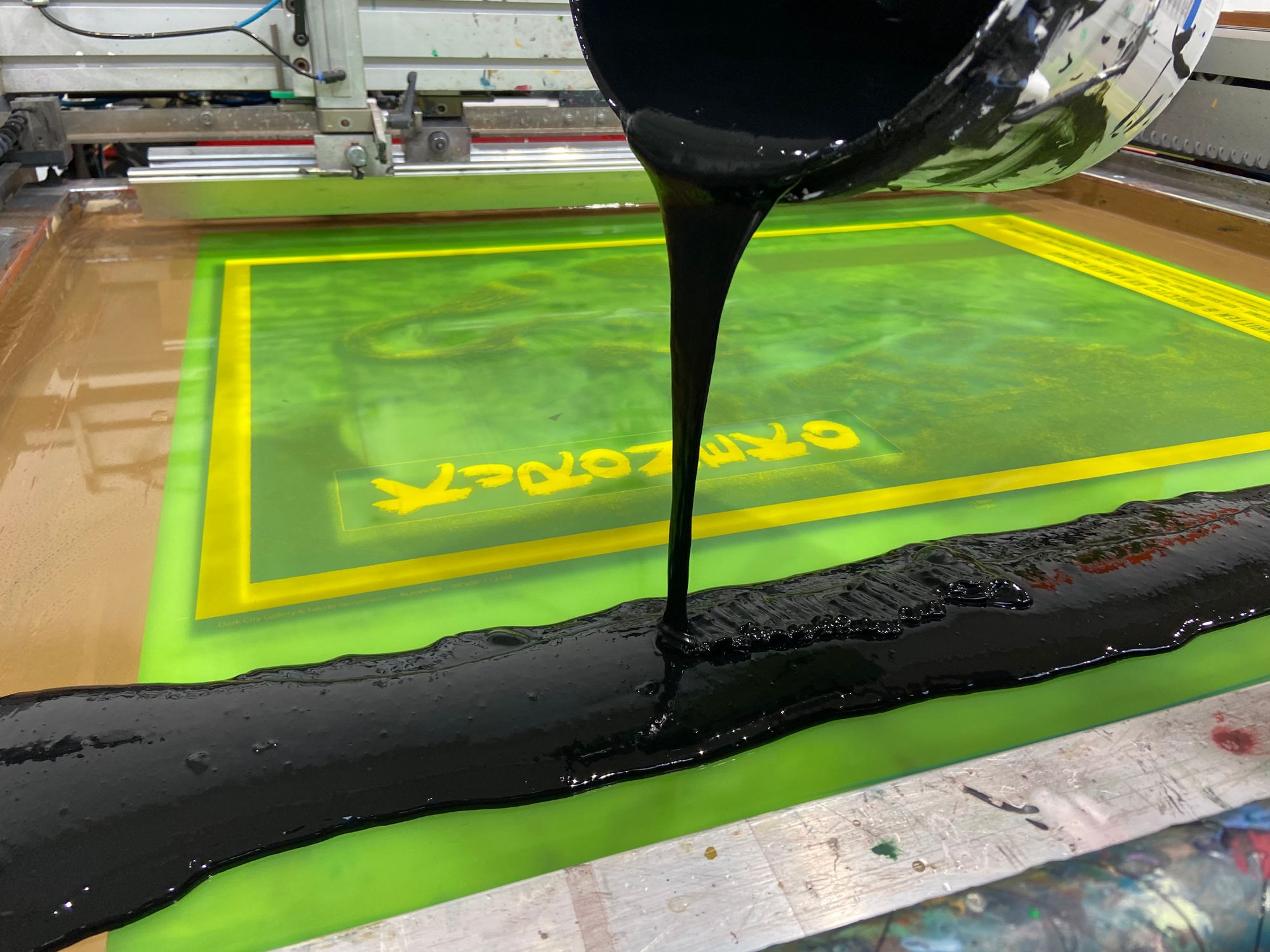

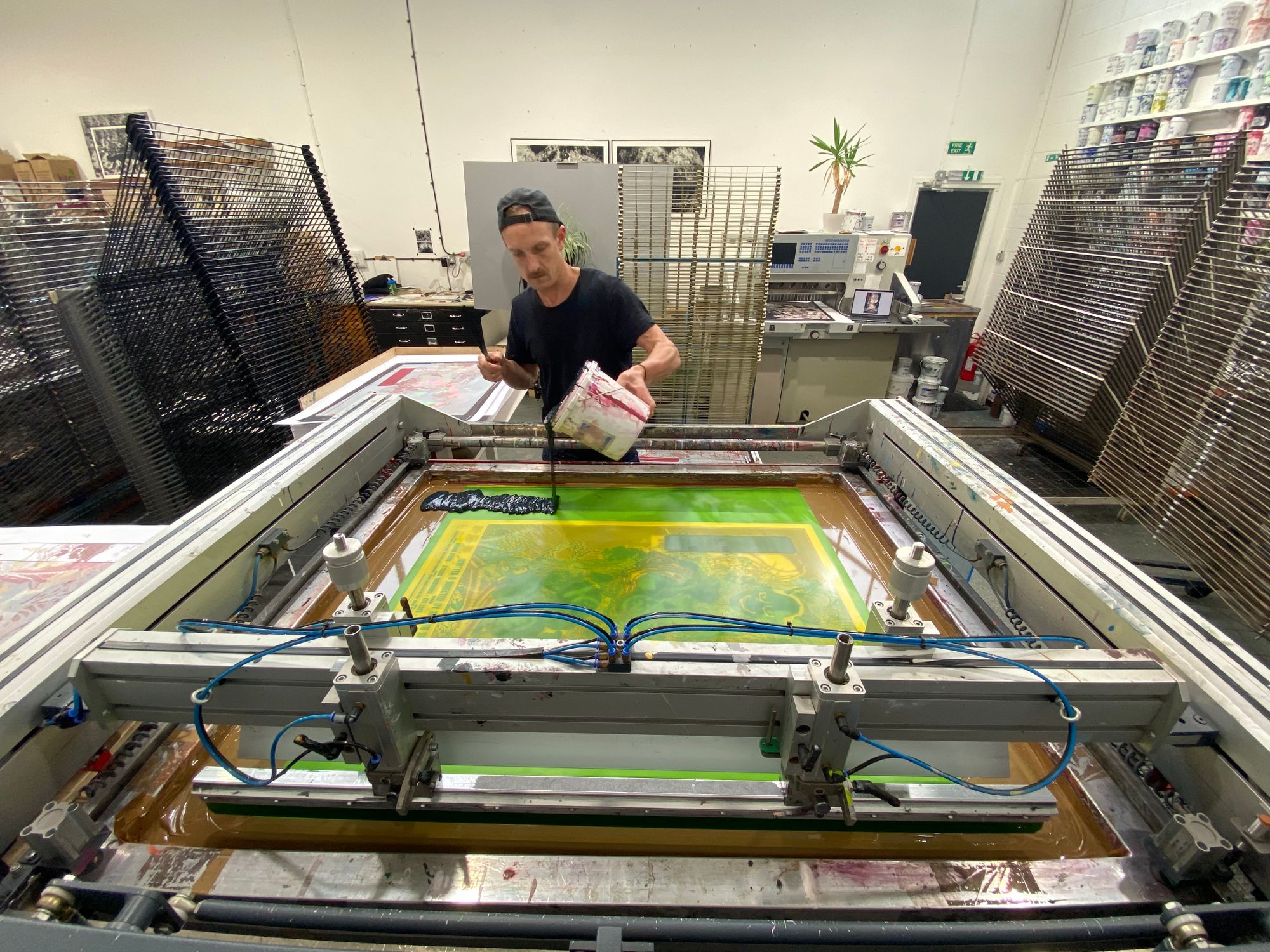

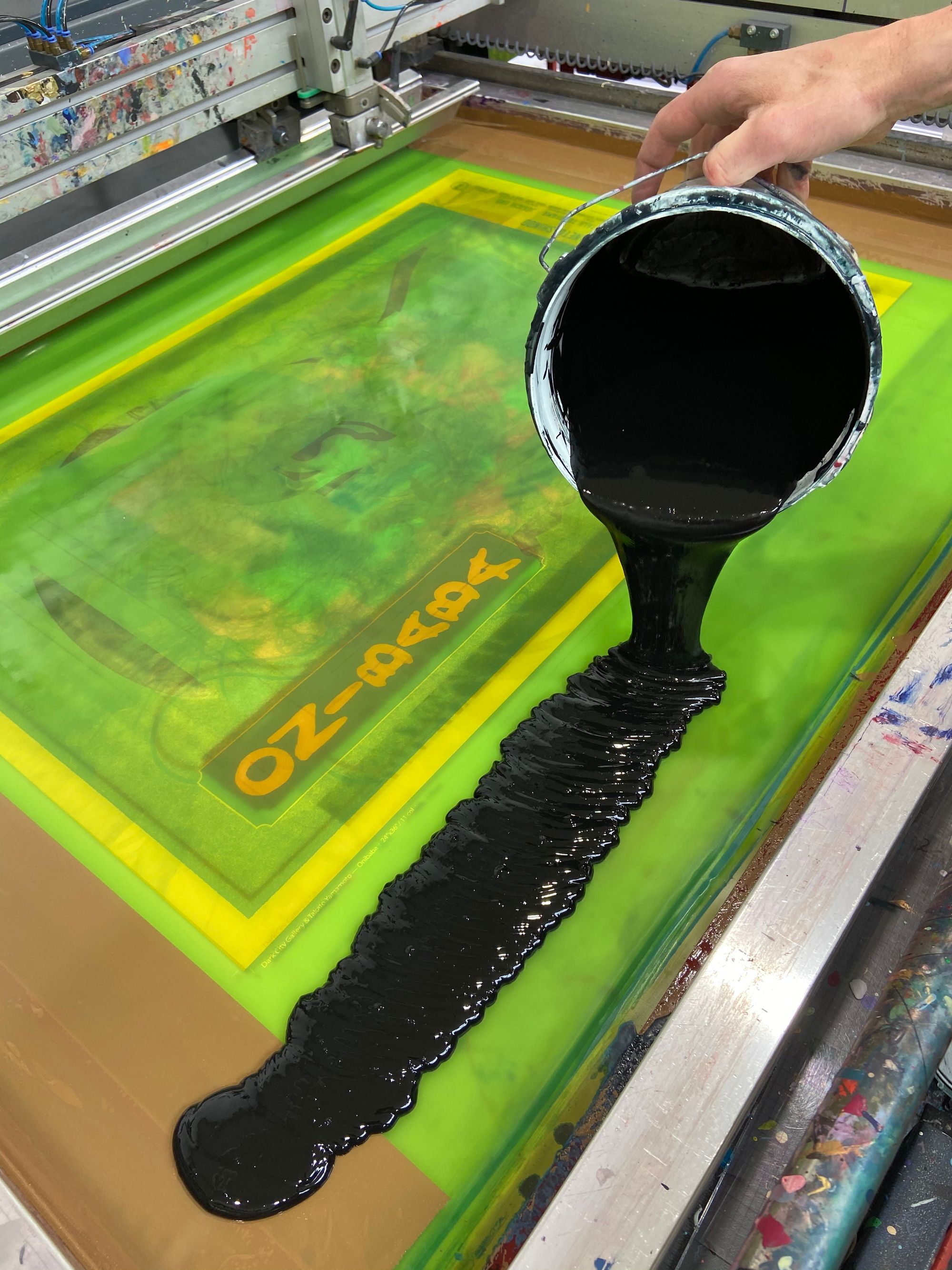

Turning Takato Yamamoto’s work into a series of screenprinted alt. movie posters presented a unique collaboration between artist, publisher, and print studio. Fascinatingly, it’s a process that bears an uncanny resemblance to that of the ukiyo-e prints of the late Edo period and bears the drawing of comparison.

While the first half of the lengthy Edo period occupied itself with simple monotone prints, created by artists such as Hishakawa Moronobu and Torii Kiyonobu and usually comprised of relatively simple black linework, consumer demand dictated that a richer, more attractive style of print be developed. Thus, azuma nishiki-e was born, a technique where ten or more colour blocks were used to create beautifully layered and intricately detailed prints. The name of this process was derived from nishiki, an exquisite silk fabric, of which the new mode of print was said to be as beautiful.

Registration marks were added to the printing blocks, in much the same way as we use these marks to align our silkscreens today, and the delivery of the final azuma nishiki-e was dependent not on the craftwork of one person, but on the collective effort of four proponents.

Eshi was the name given to the artist who drew the artwork; an artist known as horishi would carve the wood-blocks; the surishi would add colour to those blocks and produce the prints; and finally, there was the hanmoto, the publisher who typically assembled the artists, had in their sights the vision for the project and would manage the release of the prints.

Strikingly, the production process behind a screenprinted movie poster release—Onibaba and Kuroneko being fine examples of this—adheres to much the same arrangement, whereby an artist produces their beautiful work, the work is made print-ready, and is then printed, by the skill of various departments within the print studio, and the whole project only exists by virtue of the passion and vision of the publisher or gallery.

A fun aside is to consider that ukiyo-e often advertised theatre, the eshi engaging their signature style to give the artwork a unique twist. Employing an artist who heralds from the ukiyo-e tradition to create a modern-day movie poster is not such a great leap from the original intent of their adopted artistry.

When first presented with Onibaba and Kuroneko, we were instantly captivated by their unusual take on what we experience daily from the busy alt. movie poster scene. The first sight of a new poster prompts two immediate questions: What does one think of the artwork? and How will it be turned into a screenprint? In the case of Yamamoto’s posters, the answers to those questions were A great deal and With time and patience.

The poster artworks were clearly exquisite, but worth mentioning is that they were not supplied in their original condition. That is to say that the originals are one quarter the size and have no typography, and they are flat paintings. In the time between Yamamoto painting them and us receiving them, the talented Nicholas Moegly composed the posters and created from scratch the elegantly integrated title banners. The work at White Duck Editions began with separating the flat artworks, a task that took some 20+ hours for each poster.

Artwork separations of this nature can feel labour-intensive, and even once the hardest step, which is starting, has been taken, there can remain an uncertainty over which is the correct or most favourable way to turn. Akin to the hannya mask-wearing samurai in Onibaba, who is seeking directions out of the reed forest, there hangs a dread sense that perhaps no way out exists, or else the recommended path leads to the bottom of a hole — a dead-end.

"The way invariably becomes easier the further you go, and eventually those small steps lead to a realisation of the greater whole."

Of course, this is merely a light-hearted overdramatising of the process of separating a complicated artwork. It’s fun to draw parallels with the film. Appearing lost and taking wrong turns is all part of the process, to be embraced, and the real trick is to keep moving, taking small step after small step. The way invariably becomes easier the further you go, and eventually, those small steps lead to a realisation of the greater whole.

In contrast, one can only imagine the sheer volume of painstaking hours required by the horishi when carving the woodblocks for a new thirteen colour print. Undoubtedly a steady hand, distilled patience, and dedication to the craft were key to the success of those glorious multi-coloured ukiyo-e prints of the late Edo period.

In reflection, it is fair to say that by approaching Takato Yamamoto with their Kaneto Shindô poster project, Dark City Gallery envisioned a truly fascinating prospect, and was bold enough to realise it. By balancing the calibre of the films with the integrity of an artist and the appropriateness of that artist’s style, the gallery seeded the possibility of something new and truly exciting.

This confluence of the new and exciting is found in Takato Yamamoto’s aesthetic, which exists beyond the trajectory of Edo period hedonism. Its gaze is turned from the beauty and desirability of a new modern way of life to the apparent horror of its before, its after, and its ever-present underside.

Yamamoto’s artwork positions a mirror, one could say, perfectly angled to reflect the wartime uncertainty conjured in Shindô’s films—pre-prosperity, pre-social-mobility, where there is not yet a modern mode of living, there is only scavenging the wastes of class divide and revenging the fallout of conflict.

The feeling one is left with is that a perfectly inspired pairing of artist and films has been achieved. And that is something to be applauded.

Edition Details:

Poster: Onibaba & Kuroneko by Takato Yamamoto

Size: 24”x36”

Colours: 10 & 13, inc. Metallic gold

Paper: 300gsm Gmund Bauhaus

Edition: Japanese editions of 60 + English editions of 120

Printed with love at White Duck Editions